Suzanne Valadon, Feminine Modernity in the 19th Century

- Mary Hazel

- May 17, 2020

- 9 min read

A woman amongst the artists and how she challenged the traditional view of feminity

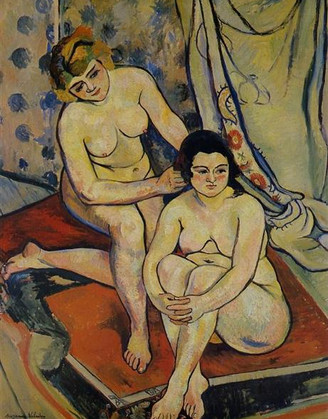

Nu au Canapé Rouge, Suzanne Valadon, 1920, Oil on Canvas, 80 x 120 cm, Musée du Petit Palais Genève

Known for her arduous relationships with the male artists of Montmarte, Valadon was more than just a muse or pretty woman. Though her affairs did aid in furthering her art career, it feels unfair to focus solely on this aspect of her life when her art represents an innovative turn in the female gaze. So, we will examine Valadon as a figure in herself, highlighting the hallmarks of her life and taking an introspective look into her art. I believe every woman should be acquainted with her name; Marie-Clémentine Valadon was and still is a strong, feminist figure.

Born in the squalors of 1865 Paris to a single and unmarried woman, Valadon grew to be incredibly independent and rebellious. She never knew her father but this did not stop her from pushing through life with tenacity and wit. She had always been enamored by the arts but had no means of partaking in any art classes. By the time she turned 11, she fully entered the workforce as a waitress, nanny, and other odd jobs. However, her favorite job was working for Molier’s Circus. She acted as a trapeze artist but her career took an unfortunate turn when she suffered an injury during a stunt. Unable to continue performing, a young Valadon began to look for other opportunities to support herself.

At only 15 years old, she met Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, a very well established painter who had his landscape work featured in the Pantheon. He was around 55 years old but he was so taken by her features and being with him provided some sort of comfort for Valadon. This was her formal introduction to the art world and her big debut as an art model.

Throughout the years, she would become the face of many great artworks. Most notably, she was one of Renoir's favorite models, using her image to pose in his cheery and fanciful Parisian scenes. Below is one of her most notorious depictions:

Dance at Bougival, Pierre Renoir, 1883, Oil on Canvas, 181.9 x 98.1 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Yes, she did have affairs with some of them but she gained something incredibly valuable from each relationship. Without any formal training, she began to learn how to create art through master artists. This was practically unheard of during the time. Her contemporaries like Beth Morisot or Mary Cassatt both came from well-off families and had some sort of formal art training (I mean jeez, Morisot was the granddaughter of the Fragonard!) but Valadon had neither of those things. Against all odds, she found immense success as a female artist.

"I had great masters. I took the best of them of their teachings, of their examples. I found myself, I made myself, and I said what I had to say."

Her most notable artistic relationship was formed with Edgar Degas. If you know Degas' character, you would know that this was quite an unusual friendship. Valadon was headstrong, free-willed, and stood against all traditional values of a woman. While Degas was a conservative from a prestigious family and a known misogynist with isolationist tendencies. Despite their differences, the pair were incredibly close and Degas became her longlasting mentor for her budding art career.

(First, Left) Self-Portrait, Valadon, 1883, Charcoal and Pastel on Paper, 43.5 x 30.5 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne

(Second, Right) Nude, Valadon, 1895, Charcoal and Colored Pencil on Paper, 29 x 20 cm, Private Collection

This is partially thanks to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec who introduced the duo and recognized Valadon's potential in becoming an artist after he saw her drawings. Valadon and Lautrec held a secure relationship at the time prior to Degas' comradery. In fact, Valadon was the model for one of Lautrec's most iconic pieces, The Hangover.

The Hangover, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1887-1889, Oil on Canvas, 47 x 55cm, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University

Additionally, the male artist was actually the one that nicknamed her "Suzanne" as opposed to her original Marie or her model name, Maria. The name is in reference to the biblical tale of Susanna and the Elders and was meant to be a joke since she was a young woman who frequently modeled for older male artists.

Susanna was an extremely beautiful wife, who sparked an immense desire in her malicious suitors. As she bathed in her private garden, two elders attempted to seduce fair Susanna but she refused their advances, remaining loyal to her husband and her virtue. In accordance with the typical pattern of these stories, these two elders felt scorned and falsely accused Susanna of having an affair with an unidentified young man. Of course, Susanna vehemently denied their claims but was nonetheless arrested and condemned to death on the pretense of adultery. Even as she stood in front of the crowd, she screamed out her defiance and renounced their claims. It was not until Daniel publicly defended her honor and proved that the two elders falsified the entire story. Though starting off as an ironic nickname, "Susanna" or Suzanne is a name imbrued with innocent seduction, immense beauty, outspoken defiance, and a fighting spirit. It seems perfect for our Marie-Clémentine Valadon, who would gain fame for her artistic endeavors as the highly acclaimed Suzanne Valadon.

Valadon's painting technique is entirely unique to herself. Unlike the whimsical blur of Impressionism or the perfected realism of academic work, her paintings were structured, colorful, with a sense of vibrancy and vitality in her linework. Often her work showcased three features: an exaggeration of defining characteristics, a combination of shading and patterned flatness, and the use of a thick black line to contain each subject accordingly.

Joy of Life, Valadon, 1911, Oil on Canvas, 122.9 x 205.7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Her earlier subjects highlighted bits of her everyday life, mostly featuring charcoal or pastel drawings of her young son Maurice. It was only in the 1890s that she shifted her work to focus on female nudes and began to slowly incorporate oil painting. Though, this was a difficult feat since she did not have the luxury of having a steady supply of oils and she had to mix the paints herself.

1894 marked a year of significant achievement for Valadon; she had five drawings admitted into the famous Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts (Salon des Beaux-Arts). In the following year, she had 12 works accepted into the Salon and her pieces were regularly exhibited in Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris. Degas had introduced her to fellow art dealers like Paul Durand-Raul and Ambroise Vollard, and Valadon steadily made a name for herself.

She did not start painting full time until 1896. After the famous disaster that was her and Erik Satie's relationship ended (Satie was being Satie and was completely heartbroken over their break), she married a wealthy banker named Paul Mousis. This marriage provided her the financial stability and free time that she needed to focus all of her attention on her artwork. With a country home in Montagny and an apartment with a studio in Montmartre, Valadon lived a comfortable Bourgeois lifestyle while still remaining in contact with the Parisian art scene. During this 13-year marriage, Valadon created incredible paintings that would define her place in history.

Now, to fully illustrate how monumental Valadon's paintings were, let's compare her work to another artist during this time.

(First, Left) Julie Manet and Her Greyhound, Laertes, Berthe Morisot, 1893, Oil on Canvas, 73 x 80 cm, Musée Marmottan Monet

(Second, Right) The Blue Room, Suzanne Valadon, 1923, Oil on Canvas, Georges Pompidou Center

As previously mentioned, another prominent female artist during this time was Berthe Morisot, one of the leading figures of Impressionism and was a part of the infamous 1874 Exhibition of the Impressionists.

If we compare the work above, we see that they have a similar subject matter and composition. Phrasing it in the most literal terms, these two paintings are of a female figure relaxing with their body alignment angled from right to left. However, if we pick apart each layer and aspect of the works, we begin to see the elements that made Valadon particularly unique:

There seems to be a difference in surroundings and clothing. Morisot's painting to the left shows a girl gazing at the viewer; she is fully dressed and in a seemingly put-together living room. Her formal attire, the painting in the back, and greyhound in the lower foreground hints that this girl is part of the bourgeois class. While Valadon's woman on the right is much more casual, laying in a disarrayed room with only her pajamas on whilst smoking a cigarette. Books lay unattended at the foot of her bed and the woman looks off into the distance. Though her economic class is very ambiguous, the chaos in her surroundings and relaxed but rough persona hints that the subject is a working woman.

We must discuss how each figure is portrayed. Morisot's painting, albeit difficult to distinguish due to effleurer painting style, seems to be the ideal female figure in the 19th century. She is comparable to the beauties in Renoir's, Monet's, and Degas' works. Light skin, red lips, soft brown hair, slender, she sits upright and holds an elegant air to her. In comparison, Valadon's woman is untraditionally depicted. She has a realistic but unapologetic feeling with her plumper figure and contrasting palette. Though beautiful, her facial features lack the delicacy of Morisot's.

Of course, amongst the most noticeable difference is the style and technique of each painting. Though Morisot originally received backlash for how lighthanded her paintings were, she became a stylistic guide to female artists - soft, dreamlike, and feminine. Despite the girl wearing a dark dress, it is still light and works within her pastel color palette. Whereas, Valadon is much more vibrant and saturated in her approach. Though the colors all work with one another, there is still a boldness and brashness about them. Her style with defined black edges comes off as "masculine" and confrontational. There is an angularity when compared to Morisot's roundness.

Now, for the best part, the biggest difference is the meaning of each piece. Morisot's work is meant to simply be a study from everyday life. The subject is actually her young daughter in their home. Valadon's painting is actually a sort of pseudo-self-portrait. She depicts herself as a contemporary Venus, harking on the renaissance archetype with a special homage to Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538). Though she is not idealized, not entirely feminine, not docile in posture instead she is rough, contemplative, intelligent, and a working woman. France's early 20th-century Venus is the modern, normal woman who lacks all the frills and gaudy prestige of a "goddess" title.

(First, Left) The Abandoned Doll, Valadon, 1921 Oil on Canvas, 127 x 81 cm, National Museum of Women in the Arts

(Second, Center) Nude with a Striped Blanket, Valadon, 1922, Oil on Canvas, 100 x 81 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

(Third, Right) The Two Bathers, Valadon, 1923, Oil on Canvas, 117 x 89 cm, The Museum of Fine Arts, Nantes

Furthermore, Valadon's work effectively desexualizes the female nude. Similar to Manet's Olympia (1863), her paintings initially shocked the art world due to her unpolished depictions. Everything is proportioned and as realistic as she viewed it, eliminating the fixation of an ideal female form. Her works show the normalcy in the bare, how being naked can be awkward, daunting, but mostly just natural. Many art historians believe that she could achieve such an honest portrayal of these models because of her personal background. Growing up in the working class and being an art model, allowed her to connect to her subjects in a far different manner than the old masters.

"I paint people to learn to know them."

Oh, and did I mention that it was unheard of for a woman to paint female nudes at this time? But Valadon did something even crazier!

Adam and Eve, Valadon, 1909, Oil on Canvas, 131 x 162 cm, Georges Pompidou Center

She painted a heterosexual couple! Unheard of! Daring! Brash! It becomes even more spectacular when you learn that she painted these figures in the likeness of herself and the younger man she was having an affair with while she was married!

And this is how the rest of Valadon's art is - brutally honest commentary on female perception, the female form, and gender norms. Prior to this, the art world was completely saturated with the male's gaze on feminity. Nude female portraits were associated with inhuman and perfected beauty, so outstanding that they had to be goddess incarnate or they had to claim it as such so the public accepted the work without batting a single eye.

Even in clothed portraits, women were associated with feminine and maternal activities like being with children, cooking, embroidery, reading, dancing, being with other females, etc. Though Impressionism heralded a "realistic" view of life, this did not seem to apply to women unless they were middle class or higher. But even then, they were still associated with the activities listed above. This is why Post-Impressionism and Valadon were so imperative in creating a shift in this perspective. They began to display how life truly is on both sides without any romanticization, especially in the everyday working class.

Though the latter portion of her life was tragic and chaotic, she had successfully made her mark in art history. As a working woman with no formal art education, she had exhibited in places like the Salon d'Automne and Salon des Independents. She also was able to regularly sell her work through the popular art dealers that she connected with. She challenged French society at the turn of an era, pushing the boundaries of tradition and paving a way for the introduction of more female artists. Suzanne Valadon was a true artist that was unapologetic in her creative pursuits, a visionary without explainable boundaries, and held a sordid apathy for the rules of tradition.

"I paint with the stubbornness I need for living, and I've found that all painters who love their art do the same."

And that's art.

P.S. If you want to learn more about her, there are some lovely lectures and documentaries about her life on YouTube. I cannot get enough of her!

Sources

Brouwer, Marilyn. “Suzanne Valadon: Artist, Mistress, Model and Muse of Montmartre.” Bonjour Paris. May 17, 2017. https://bonjourparis.com/history/women-who-shaped-paris/suzanne-valadon/.

Marder, Lisa. “Suzanne Valadon Artist Overview and Analysis.” Edited by Rebecca Baillie. TheArtStory.org. August 13, 2019. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/valadon-suzanne/.

Michalska, Magda. “Suzanne Valadon: The Mistress Of Montmartre.” Daily Art Magazine. September 23, 2016. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/suzanne-valadon-mistress-of-montmartre/.

“Suzanne Valadon Quotes.” Art Quotes Categories. Accessed May 18, 2020. http://www.art-quotes.com/auth_search.php?authid=7252#.XsHRmhNKg_U.

Comments